A handful of years ago I was asked to join Western Mining and build a major part of their new AUD 1 billion fertiliser facility in far north western Queensland. Western Mining was then led by two icons of the Australian mining industry, Hugh Morgan and Andrew Michelmore. The facility was going to built at a remote site called Phosphate Hill. I grew up in areas like Phosphate Hill so I was excited to be outback again.

I arrived on the project when design and build tenders were being evaluated in WMC offices at Riverside Centre, 123 Eagle Street, Brisbane, Australia. Coming from the “grubby” oil and gas game, you gotta love the Australian mining business: red carpet and art work in the in the foyer and lobby areas and almost-gold faucets in the toilets. I was the client engineer in charge of the Phosphoric Acid facility and my project engineer was going to be from Bechtel. Together we would be taking phosphate rich rock and dissolving it in sulphuric acid to make feed stock for fertiliser. Fun stuff. I was 26 years old

The Phosphate Hill Fertiliser Facility, North West Queensland

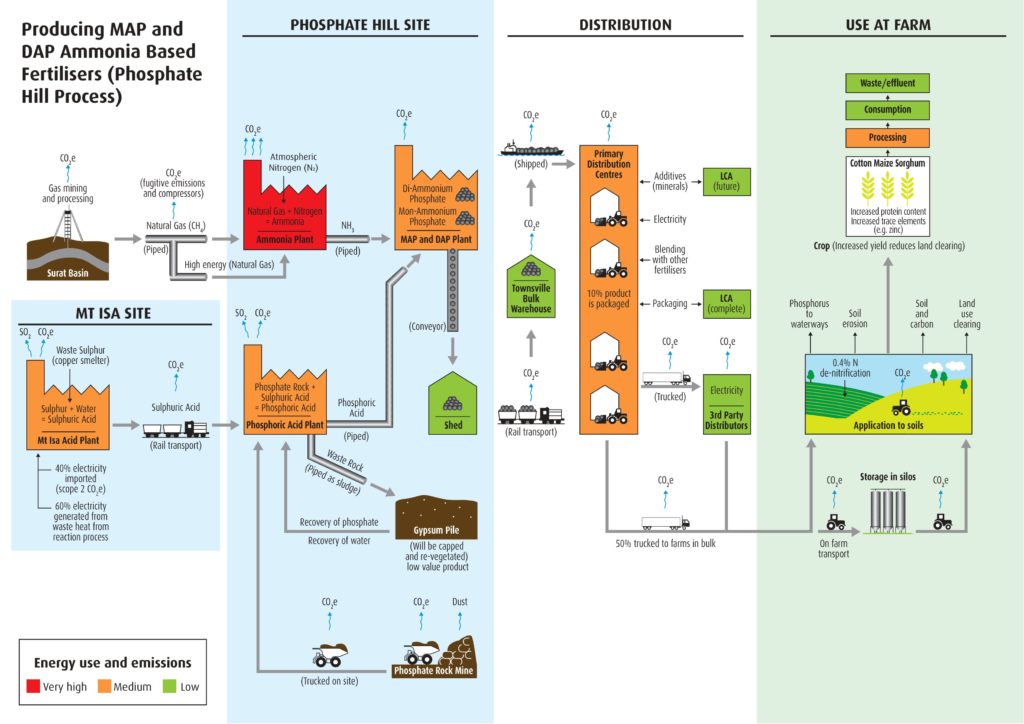

The facility manufactures 1,000,000 tonnes per year of ammonium phosphate fertilisers and is located approximately 1,000 km west of Townsville on a large phosphate rock deposit. The entire operation combines world-class, low-cost manufacturing facilities spread across multiple sites. At Phosphate Hill, ammonia is produced from methane gas sourced Santos’s Ballera gas facility located 800 km to the South. Sulphuric acid is supplied via specialised GATX rail cars delivered by train from a purpose built sulphuric acid plant located 150 km to the north at Mount Isa. There, waste gases containing sulphur are collected from Xstrata’s copper smelting facilities and converted into acid. To the east in Townsville there are the warehousing and export port facilities. During construction approximately 1,000 personnel where located on site, housed at a camp at the nearby Monument. Now a crew of about 250 personnel cover the operations of:

Built by WMC Resources, owned briefly by BHP, now owned by Incitec Pivot

– Mining and Gypsum stacking

– Beneficiation

– Ammonia production

– Phosphoric acid production

– Granulation

Bechtel where wrapping up their assessment of tenders so there wasn’t much to do except watch what was happening. And then visit all the locations. The chosen contractor was a consortium of Norsk Hydro‘s using hemihydrate technology (based in Rotterdam, Netherlands), Mitsui process design (Tokyo, Japan) and Clough detailed design and construction (Perth, Australia). Norsk had operating plants in Thailand and Jordan, so within a few weeks of arriving in WMC’s offices on Eagle Street, three of us from WMC and the Bechtel project engineer went on a world tour taking in Japan, Thailand, Jordan and The Netherlands. It was 1997. The trip is a story in itself, but most memorable was the introduction to Japan which I savoured and repeated several times since including an extended period I call my “Japan time”. There’s a reason why Toyota is the best car in the world.

For fun, I formed the social club during the construction period and the club became responsible for beer purchases. We did ‘beer and barbies’ – this was Australia after all. We averaged 2 cases, or 48 375 ml cans of full strength beer per person per week. That was a “six pack” every night for every person in our 1,000 construction crew for 3 years. That was a lot of beer for a construction site with zero alcohol policy. I’m surprised that only 1 person was killed during the work.

As an aside, Bechtel have an amazing story. Still a family owned business, it was founded around 1898 and their key to success is taking a 5% commission on all procurement they manage. And they want to manage all of it. [Pro tip: always be between those that can, and those than can’t. Be he middle man!].

I owe a lot of my lessons to the head of my construction consortium, Michael ‘Mike’ Anderson. A veteran in project management, he knew how to build a plant and he knew how to make it profitable. I just had to watch and learn. He used the most wicked, and most effected application of critical chain theory I had ever seen. His got his team to make estimates for their respective work scopes: BOQs, GAs, structural, concrete, tendering etc. Then he got his project planner to make two plans: one with the information as given. And a second plan with all of the times simply cut in half. He then put the first plan into a locked drawer and got his planner to swear he would never tell anyone about the first plan. The project then proceeded to run on the second “compressed” schedule. It was what I call planning to win as opposed to planning to fail as traditional Gantt chart planning does. It worked perfectly, with Mike coming in 6 months early on his contract. My task as the client then evolved into making the path as smooth as possible for Mike and his team to do what they had to do: build a world class phosphoric acid plant.

One of the things that struct me was the laissez-faire, relaxed nature of the WMC/Bechtel management office. I had come from the oil industry. Among my previous gigs after the refinery, were as project engineer for Chevron’s USD 4.5 billion gas pipeline from their Kutubu gas fields in Papua New Guinea to Gladstone; and saving the Moonie to Brisbane oil pipeline which was in danger of being washed out across it’s multiple creek crossings and Santos was stalled on the fix for more than 2 years on what to do. (More stories there also). Why so relaxed for such a huge facility? It wasn’t until I walked into my first phosphoric acid facility in Thailand to understand why. There where no consequence of failure. If anything went wrong, it would just be a plop on the ground, not an explosion in the air. It was very hard to get killed in a phosphoric acid plant. Once I realised this, all stress about the project fell away from me. Nothing could go wrong. Well almost. We “forgot” the fluorine. More on that next.

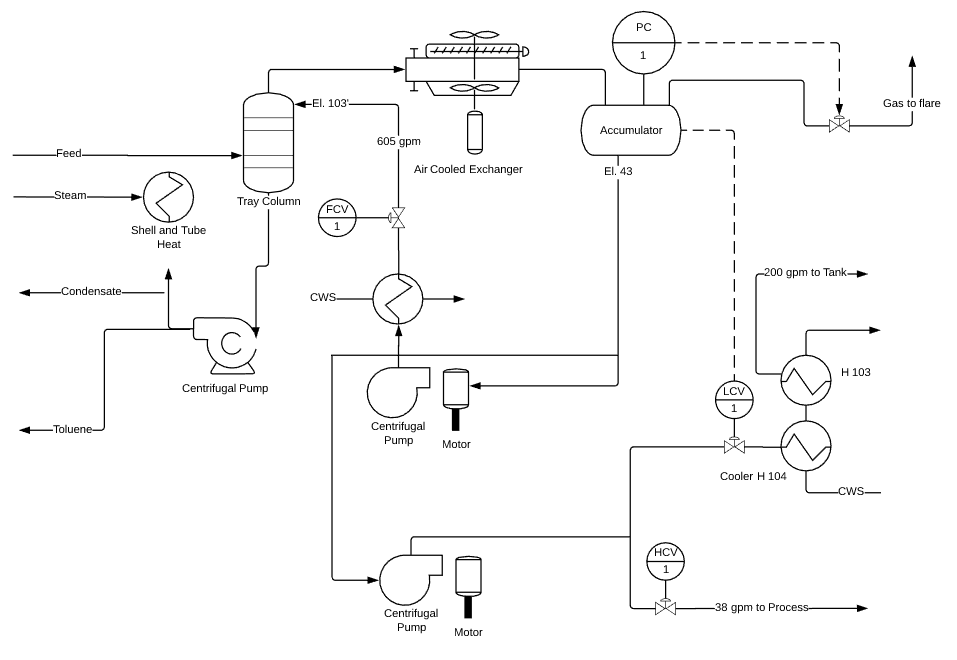

Once the process design and preliminary layouts where done we where ready for HAZOPing. Coming from the oil and gas industry I was an expert, having re-designed the entire HAZOP procedure at BP where I was running 1 or 2 HAZOPs each month. Each were small – only a few hours sometimes, but every HAZOP runs the same. For Phosphate Hill we planned to HAZOP Japan for about 2 weeks to go through the 100 or so P&IDs we had. On the very first day we spent the entire day being ‘taught’ how to HAZOP by an ex-Shell consultant. We spent the entire day HAZOPing a 3 meter deep sump that ”could’ occasionally get hot water into it… It was hair pulling stuff. It was so draining that we actually forgot to properly evaluate the floruie coming from the rock. Passed off as “insignficant”, the singficant amounts of flourine in the rock caused massive problems later on during operations with staff having to wear alsmot full hazmat suits to go anywhere near the filter belts. When looking back, one of our process engineers had only ever worked on low floruine rock. If I wasnt’ so bored at the HAZOP I might have raise the issue to consider how much gas would be released compared to other sites worldwide. We would be one of the largest.

The most immediate task I set for myself after the world tour and I was back in the office in Brisbane was to create a battery limit interface for my plant. There were hundreds of interactions coming from multiple contractors into (and out of) the phosphoric acid and I was the only one who really cared that they all worked. Even my contractor, Mike, ever playing the contractor game, would come up with inputs and outputs that simply didn’t align with other contracts. Granted however he was totally organised and no one else was. He was first so others had to catch up to him. So I became the negotiator in-between them all. After all, I wanted my plant to work. And talking with everyone else in the project I got to learn about how everything worked.

One of the most revealing events in this process was when I went to the project’s chief scientist with two pieces of paper: one was what the specification of what the Benefication plant was going to produce (ground up wet rock) and what the phosphoric acid was expected to receive (also ground up wet rock). They where different. At first I thought it would be a simple matter of alignment. A casual hallway chat. When nothing happened, I escalated to email. And then further discussions. This continued for some weeks until I was told to “just let it go. Ignore it”. When one of the senior managers on the project arrived to the office in a new Porsche a few weeks later, I was started to get the idea.

But I was enjoying the complexity of the project. From a office overlooking the Story Bridge and the Brisbane River in one of the world’s most prestigious buildings, after a few months I moved to the site at Phosphate Hill and was baking in a construction donger before the air condition had been installed. For next several years I watched another creation of humanity come together and rising out of the earth.

Over the duration of the project I kept negotiating my salary higher and higher until I was told that I was the highest paid member of the staff at my level. A few years later when I was consulting at Mt Isa mines and at the deepest point in their 3,5000 deep copper mine, I became friends with another engineer who told me he had been offered a job at WMC to run the phosphate acid project on such-and-such a date. Remembering back, that was my position! And it aligned with one of my negotiation pay raise cycles. I had obviously negotiated too well and my new friend was offered my place, but at even less than what I had started at WMC. He – obviously – didn’t accept. Again it told me about the games going on behind the scenes on the project.

I had drawn up a Gantt chart on my office white board which remained to the end of the project. It showed how the how the entire project would be delayed by anywhere from 12 to 18 months and how my phosphoric acid plant would be 6 months early. It was always an interesting talking piece with the other team members.

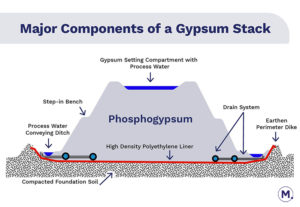

When drawing up my battery limit management plan, it was also apparent that the Phosphogypsum waste coming from my plant wasn’t being addressed. When I raised the question, again I was told not to worry about it. That is until later. The gypsum stacking facility had been entirely forgotten from the project.

Eventually I was asked to also take care of the Gypsum stacking facilities – not a small thing as you can see from the google map. When the answer was “no” to my question, “would I be paid more?”, I declined. However I picked it up some time later because I was getting bored waiting for the rest of the project to catch up which was by now clear to everyone else running late. So I had a bunch of time up my sleeve. I also met an awesome chap who fixed dirt like I’ve never seen it fixed before. He was a civil construction guy brought in to build the earthen dams to hold millions of tonnes of future accumulation of phosphogypsum forever. Yes, there’s no apparent commercial use for these huge piles of white stuff.

Through my time building the gypsum handling facilities I met and worked with one of the former advisers to the Queensland Premier, Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen. This person, Mr Smith will do, was the architect of the entire North West Region Minerals province and the reason why the Phosphate Hill actually went ahead at all. Mr. Smith had an ambitious plan. He brought together arguing, warring government and semi-government factions of the likes of Santos, Queensland Rail, Mount Isa Mines and a bevy of private companies. Over 2 years he negotiated and cajoled to bring everyone into alignment: to install gas pipelines, have lower rail transport prices, make available port land in Townsville, and share port facilities with the coal industry amongst many other key factors. Twenty contracts where signed in 2 weeks at the end of those 2 years and the Phosphate Hill Fertiliser Facilities became possible. It was incredible to hear his story as he regaled them to me in the best business clubs across Brisbane.

One day Mr Smith casually slid two massive tomes across the table to me. Each was 3 inches thick, cheaply bound in green cardboard and red spiral spine wire. I asked what they were and he replied they where the project manual for Phosphate Hill, in two volumes. Wow! I never knew these even existed. For days after I plunged into them and their 1980’s typewritten paper. I was amazed that the entire project existed in such detail from the mid 1980’s. In fact every single problem that had delayed the rest of the project had been identified, thought about and a solution or solutions already determined and documented. If everyone on the project had read this report before the project started hundreds of millions of dollars would have been saved in mistakes, cost overruns and simple ignorance. But then, I realised that wasn’t the main agenda. In the midst of mistakes money can be made.

As Phosphate Hill was being commissioned someone else handed me the book Cash Flow Quadrant, by Robert Kiyosaki, and I didn’t look back.

In a few days I read the book, consuming it with zeal. Suddenly I had all of the vocabulary I didn’t have before. All the knowledge that had been bouncing around in my mind came into alignment. I was financially literate. Well 101 level anyway. Within 6 months I was out of WMC, the project was into operations mode now, and within a further 3 months, after looking at more than 1,000 prospect rental properties across Australia, started on my property acquisition spree. I remembered Kiyoski’s advice “you only make money when you buy”. That leads to another story of how I turned AUD 25,000 into more than AUD 1,000,000 in less than 18 months. I’ve only ever consulted for fun thereafter.

So, reading is the path to success. That was a clear lesson from my time with WMC.

Recent Comments